Ship software, not code

Note from the editor. That’s me, Gabe. I’m the editor. I’ve had this blog post in draft status for a while, originally creating the outline for a possible conference talk. I didn’t write it to be negative about any particular software, language, or approach. However, in the past day I’ve done some software installing and found myself experiencing much of what I wrote below. However, it’s still only a coincidence and I didn’t write this to be on the offensive against any one project.

Software and code Link to heading

Same thing, right? Well, no. You write code, and then you turn it into a software product people can run. I want to discuss how they are very different things, and the differences make a significant impact in how we approach empowering users with new tools and technologies. Especially in a time where giving people legitimate alternatives to centralized, big tech services is more important than ever.

So what is software? Link to heading

Take a moment to visualize what software is. What does it look like? Some may think that’s a stupid question to ask about something so abstract, but it’s not at all abstract to me. When you say “software” this is what comes to mind.

I think about walking into any big box store in the late 90s/early 2000s and going to their electronics department to see things like Microsoft Word, Doom, Print Shop, or Lotus 123 on the shelf. You could grab a box, bring it home, put it in your computer, and off you go. You were killing monsters, spreadsheeting, or printing out a banner before you knew it.

What does this have to do with the topic of this post? Let’s start by picking a box of software off that shelf and ask yourself:

- What programming language was the software written in?

- What tools were required to build it?

- How were the dependencies managed in the development of this software?

- How is data persistence handled?

Let me make this easy for you, the answer for all of the above is “who cares?”.

What about modern software? Link to heading

Let’s ask those same questions for a modern piece of commercial software. While it’s not as common these days to walk into a store and bring a box home, you still buy it from a different kind of store and install it on your device.

The answers to the questions are the same. Nobody looking to run this software knows or cares how the software was built.

Let’s look at a third example. This time some non-commercial, likely open source software. Say you wanted to host a little photo gallery to share pictures of your vacation with your friends. While it’s not boxed software, and it’s not something from a centralized App Store, it’s still fair to assume that we can just download it and run it. It’s just software, after all.

Obviously something is different here. You’re being given code. And because of this not only do you know the answers to the original above questions, you have to know the answers in order to begin the process of running anything.

Obvious disclaimer Link to heading

While I don’t feel like I’m overly exaggerating in this post, I do want to make it clear that I don’t think everything is as easy as one command or one click.

- Obviously as requirements increase then users of software have to be aware of and meet those requirements. However, if one person wants to run one piece of software on one computer then yes… it should be relatively low effort to allow them to do so.

- Some projects make this stuff a priority and package their Javascript or Python in a way where people can use it, but they are in the minority.

- If you only write software for yourself, to run personally or in a software-as-a-service scenario (a more and more common occurance), then do whatever you want.

- Lastly, I’m not saying that I’m perfect, but I do try to think about these things. And I’d like you to think about them with me.

How did we get here? Link to heading

I wouldn’t normally blame the language for the output, but the language choice and tooling surrounding each language has created a cultural change around shipping software.

As the open source movement exploaded, and languages like PHP, Javascript, Python and Ruby became popular, fewer and fewer people were writing software that was natively runnable. Similarly you have languages like Java where you were required to have an entire virtual machine installed to run the software.

As “shipping source” became more common, the next step was inevitable. Developers simply pointed potential users to a repository of raw source code and said “good luck”.

And while I’m being harsh here about choices we developers have made, I don’t place all the blame there. The developers using these languages haven’t been shipping software in a self-contained way because these tools simply don’t have a first-class way of doing so. However it is our fault when we collectively choose a tool because of the developer experience without thinking about the final shipped experience. It doesn’t seem like many Javascript developers are thinking “maybe I shouldn’t require my end user to know what npm is or force them to install node before they can play the game I made.”

And then the databases Link to heading

To make it all worse, we started treating database servers as a default dependency for almost any kind of software. Even for the most simple of data persistence cases. This means not only does a user have to understand how to get your software up and running, they have to understand how to spin up an entire database server just because you, as a developer, prefer to use PostgreSQL or MySQL. And don’t get me started when things require a relational database server AND Redis just to get running.

The Docker Workaround Link to heading

As managing source code became more complex and developers wanted a way for potential users to not have to deal with it, many projects simply defaulted to shipping pre-configured container images as their only installation method.

But I think we can all agree that if your software is so complex to install, with so many dependencies, that you’ve given up, and started shipping entire copies of a computer with it pre-installed, something is wrong.

Why does this matter? Link to heading

The responsibilities and knowledge required to be a software developer, such as managing runtimes, installing dependencies, and running raw source code, have been duplicated and handed to the user to also be made their problem.

Who cares? Link to heading

People who run open source, or non-commercial software are deeply knowledgeable about package managers, tool chains and programming languages, and I shouldn’t be so worked up about how software is shipped to them, right?

Well there lies the problem. We need to build solutions for anybody who wants it. The world is falling apart right now due to the centralization and control of big tech. We need small tech to empower individuals and fight back. In order for that to happen everybody needs access to the tools we’re building. This means more single-user software that you can download and run without heaps of dependencies, just like the boxed software we talked about above. Just like the software you can find on your phone’s app store. Software is meant to be run.

If you build a free and open source Yelp alternative for people it doesn’t matter how good it is if people get stuck fixing Ruby Version Manager conflicts. If you build an awesome game, but your users only have python2 and you wrote it for python3, that’s one fewer person to enjoy your game. If you build a self-hosted Eventbrite but the community leader doesn’t know what Postgresql is, then what was the point of building it?

Besides, even if the software was “just for techies”, don’t they deserve a nice experience setting up your software, too?

So let’s fix this Link to heading

Ship binaries Link to heading

The good news is I think we’re getting on the right track. Languages that focus on shipping compiled, runnable binaries are on the rise. Go and Rust being two examples that are visibly changing the culture of shipping software to users. This needs to continue.

I’m not saying don’t use Ruby, or don’t use Python. But what I am saying is if you’re writing something with the goal of other people running your software, you need to ship software they can run. And some languages are simply going to be better than others at having first-class ways to accomplish that.

Databases Link to heading

Let’s stop using external database servers as the default. Start with an embedded database like SQLite. If your software has the requirements then you can also offer a migration path to a larger database server. But a local, embedded database is fine for many more things than you think.

Hosted one-click installs Link to heading

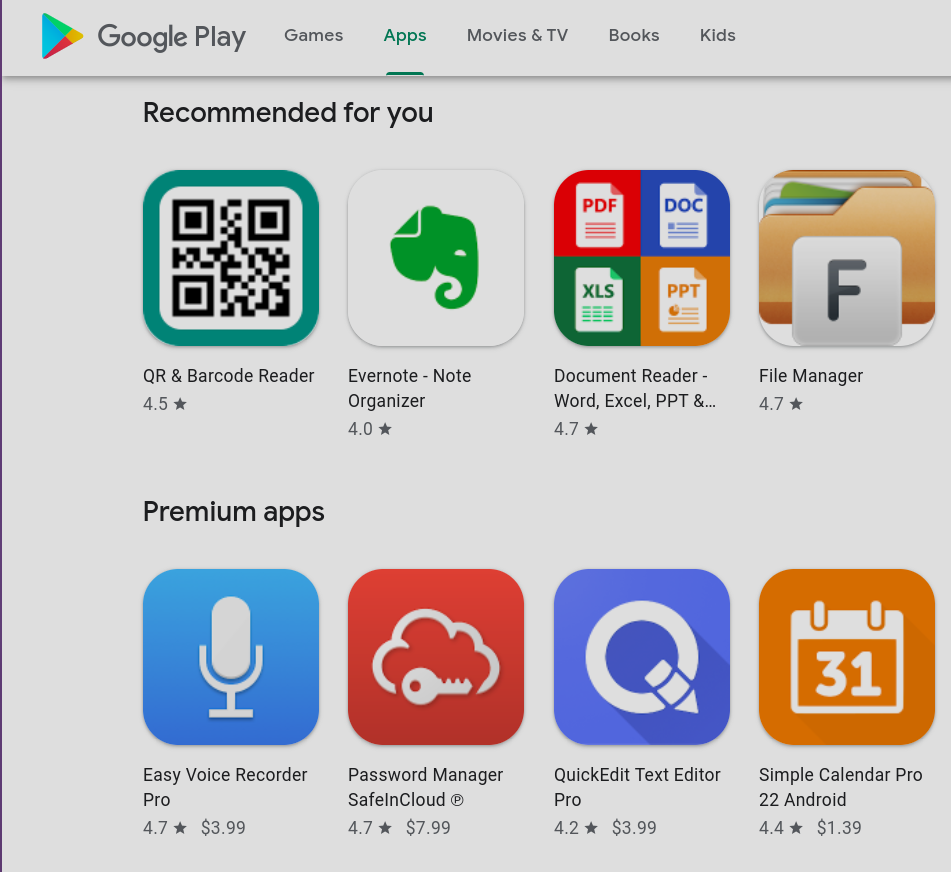

It’s a bit off topic, but it’s still completely relevant in making sure that more people can install your software. Sure, this involves “the man”, but it’s a decent compromise. It’s free for you to make sure your software is available on the marketplaces of major hosting providers and it allows people who don’t have the physical resources to run your software using monetary resources instead.

In conclusion Link to heading

Write code with the intention of shipping it as software. Code is not software.

- Let’s empower more people by getting more runnable software into their hands.

- When building, pick tools that let you do that.

- Chill it with the database requirements.

- Git and Docker aren’t installation methods.

- Any piece of software that requires the user to care, or even know, the details behind the scenes have failed the user.

- If you do exclusively software-as-a-service stuff and nobody needs to run your code but you, then do whatever you want.